Summersault

my notes on Vivendi news

somersault - a gymnastic move in which you lower your head almost to the floor and roll forward so your feet flip over your head. Fancier somersaults are done in the air, rather than on the ground. Comes from the now-obsolete French sombresault, from the Latin roots supra, "over," and saut, "a jump."

“Das Gegenteil eines Fehlers ist ein anderer Fehler”

[the opposite of a mistake is another mistake]

(Bernard von Brentano, Theodor Chindler)

On a Friday in the Spring of 1998, the stock of Compagnie Générale des Eaux jumped by 8.6% because, writes Les Échos, it had announced that the new name of the company would be “Vivendi”. This Friday (18.07.2025), a generation later, the stock of Vivendi advanced 13.3% on some more fundamental news: the reaction of the french market regulator AMF to a stunning decision handed by the Paris Court of Appeals in April of this year.

Flashback

Let’s rewind: Bolloré SE, the main holding company of the Bolloré family (market value 15bn€, freefloat ~28%), together with other family entities, last year held slightly less than 30% of Vivendi SE. Crossing the 30% holding would entail an obligation to submit a bid for the whole company, per AMF rules (Article 234-2). This is something that Bolloré probably wanted to avoid - Bolloré SE even sold nearly 180m€ of Vivendi shares on the market in May 2023 when the company decided to cancel shares it had bought back, to avoid crossing the 30% threshold.

In December of the same year, Vivendi announced it had hatched a plan to split itself into four companies. A big task that would take a year to complete. The rationale was to reduce the “conglomerate discount”. But there also was a neat trick. Vivendi was “taking advantage” of the conglomerate discount to buy back its own shares (up to nearly 4%) on the market. Since the split shares would only be given to shareholders, Bolloré SE would own more than 30% on the day of listing of the split entities (Havas NV, Louis Hachette Group and Canal+) - thus “elegantly” skipping the threshold for a mandatory bid.

This obviously did not please some minority shareholders of Vivendi which had long bet on a mandatory offer for Vivendi by Bolloré, and took their protest to the regulator and the courts.

The regulator had decided in November 2024 that Bolloré SE would not have to submit a mandatory offer according to Article 236-6 of its rulebook.

“you have control”

This is where it gets very technical. The market regulator has its rules, but there is also the commercial law (code de commerce), and they have different definitions regarding what it means to control a company. If you are not into technical legal stuff, I have created a simple “meme” summary for you:

The code de commerce was created under Napoléon I in 1808

Vivendi was créated (as Compagnie Générale des Eaux) under Napoléon III in 1853

Therefore, the code de commerce has seniority and Bolloré must make a bid for Vivendi.

This is obviously a joke, but this case is really a good example of how legal uncertainties or unclearly formulated notions can have a huge impact.

Let’s dissect what’s going on.

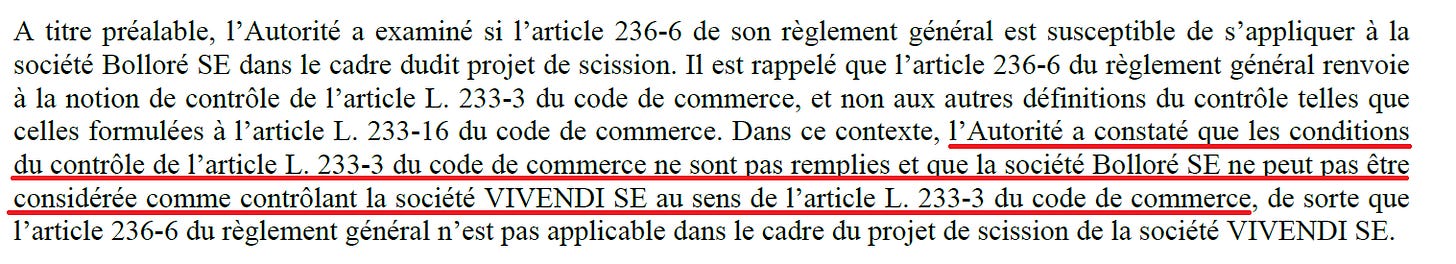

Vivendi was proposing to its shareholders a vote on the four-way split. A favourable vote would have a deep impact on the structure of the company, it is thus within the purview of Article 236-6 of AMF rules - which states that if a controlling company according to the code de commerce submits such a “deep change” proposal, the AMF has to examine wheter a mandatory bid has to be made. The AMF examined whether Article 236-6 was applicable, but concluded that Bolloré did not control Vivendi (in the code de commerce meaning) and therefore, no bid was required.

How does the code de commerce define control? This is what L.233-3 of the code says:

someone controls a company if

he directly or indirectly holds shares giving him a majority of voting rights at an AGM

he solely holds a majority of votes according to a pact with other shareholders

he factually determines the voting outcome at an AGM by the voting right he controls

he is a shareholder and has the power to nominate/revoke a majority of the board members.

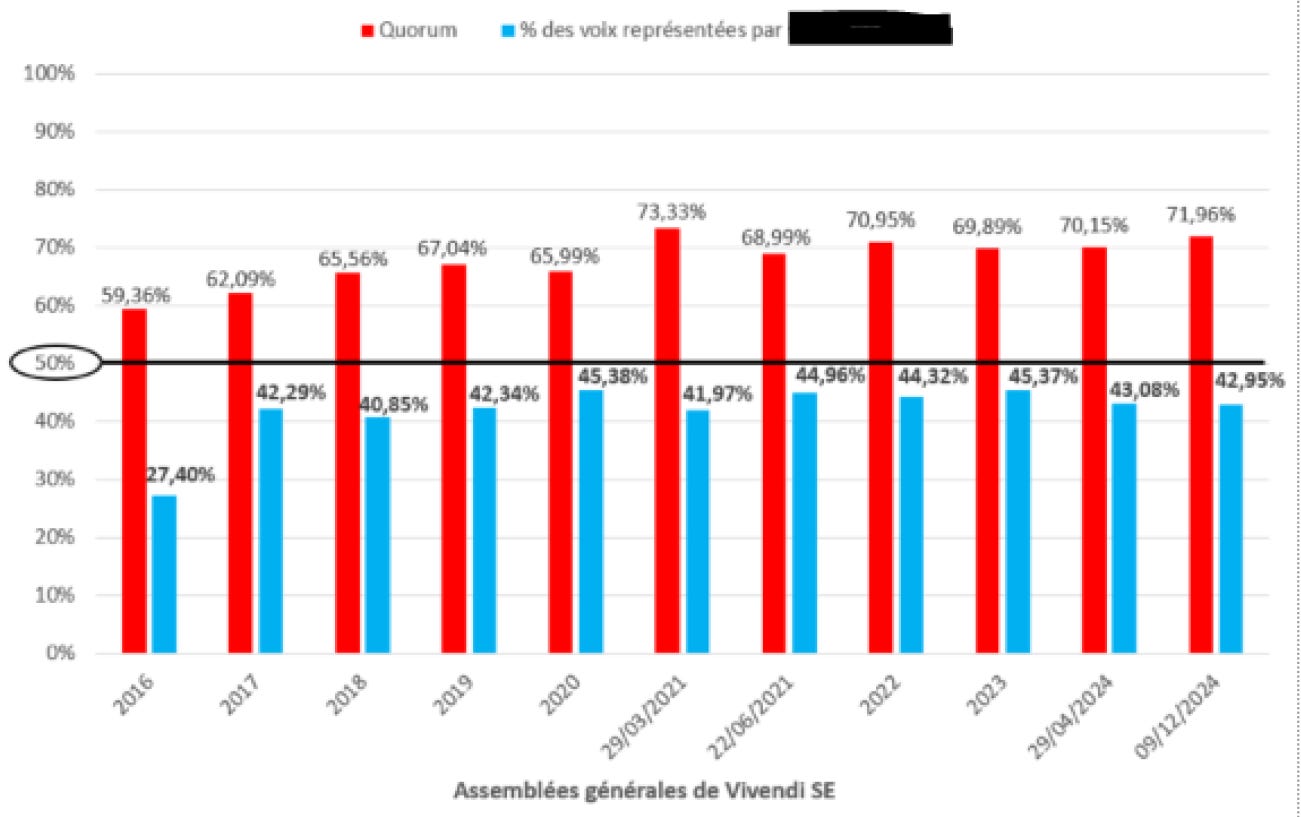

Now, Bolloré never had a majority of voting rights at a Vivendi AGM, but he was “close”:

The Paris court of Appeals overturned the AMF decision with the following reasoning (If you want to read the full decision of the Paris Court of Appeals, it can be found here):

Simple control does not force a mandatory bid, but exerting this control does (the reason of existence of Article 236-6 of the AMF rules)

Control should not be interpreted narrowly (“thresholds”) when it comes to the protection of minority shareholders, but holistically.

The quality of control by determining the voting results at an AGM should thus consider the voting rights exercised, the quality of “main shareholder”, his strategic position during the AGM, his notoriety and the concentration or dispersion of votes among the public shareholders

V. Bolloré (and his various companies) could exercise 30.94% of all voting rights, he was thus clearly the dominating/main shareholder, and the only “industrial shareholder”. The shares held by the public are highly dispersed. Since not all shareholders attend the AGM, he also had an effective blocking minority.

V. Bolloré has an “undeniable notoriety”, is experienced in Vivendi’s sector of operation, which would reinforce his “credibility” during an AGM. He had been chairman of the board for many years, before his son Yannick succeeded him. His role as president of the AGM, chairman, main shareholder and only industrial shareholder would confer him special authority to nominate new board members (as evidenced among others by the election of his sons as members of the board)

looking at the turnout and voting results of the ten last AGMs of Vivendi, all resolutions for which Bolloré has voted have passed, and his average voting power was 43.39%, just 6.61% below the majority of 50%.

The court was thus of the opinion that V. Bolloré controls Vivendi in the code de commerce sense of L.233-3 Number 3 (“factually determines the voting outcome at an AGM”).

What a mess

While being a very good decision for the protection of minority shareholders, the Court of Appeals decision creates a big headache for both the regulator and Bolloré and Vivendi:

the split had already occured as it was previously green-lit by the regulator and the Vivendi AGM, without waiting for the Appeals Court decision. The “damage had been done” and it seems impossible to force a retroactive bid on the split entities, listed in Amsterdam, London, and Euronext Growth, and whose shareholder base has already changed a lot since the split. The AMF would thus have to decide whether a mandatory bid has to be made for an entity that does not exist anymore in its previous form.

it causes the exact situation that Bolloré had tried to avoid: a mandatory bid for Vivendi.

Vivendi and Bolloré have both already filed an appeal with the french supreme court at the end of April, the decision is still pending.

“When the facts change, I change my mind”

The regulator was now in an impossible situation. The Court of Appeals ruled that it had made a mistake by not examining whether Bolloré should make a mandatory bid because of the Vivendi split proposal. It would now have to re-examine its decision but even if it came to the conclusion that a bid had to be made (which is implied by the Court of Appeals ruling), it was in no position to enforce it anymore since the split had already occurred, and the split entities were beyond its ruling (especially the listings in Amsterdam of Havas, and in London of Canal+). Lawyers may still point to the fact that all entities remain french taxpayers and have their HQ in France, but that - again - will be a matter of dispute. As well as which shareholders would benefit from a bid (those holding the shares before the split, or those that purchased them afterwards?). Anyway, the regulator would have to reverse its “wrong” decision, and the new decision was most probably bound to be “wrong” again.

Which brings me to the opening Quote from the book Theodor Chindler that I inserted at the beginning: Das Gegenteil eines Fehlers ist ein anderer Fehler. The author of the book was the father of my PhD advisor, and he loved quoting this sentence:

The opposite of a mistake is another mistake

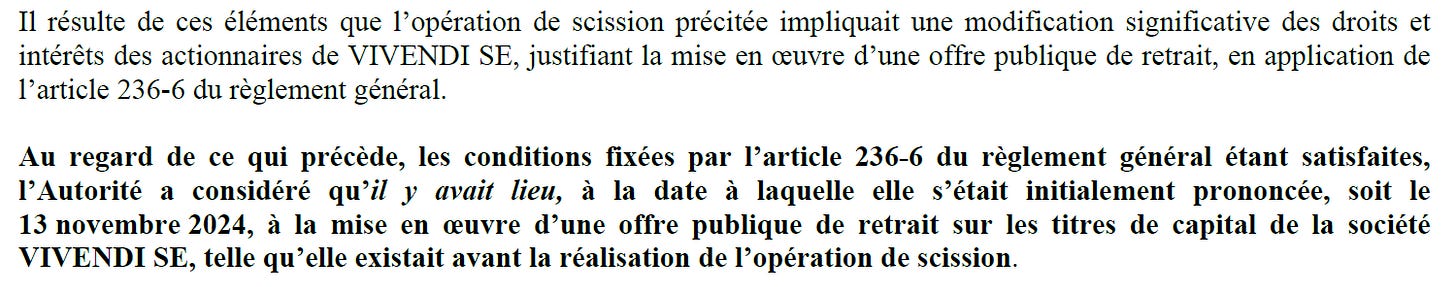

The new AMF ruling was released yesterday. In light of the “new information” that V. Bolloré does, in fact, control Vivendi SE, the AMF ruled that the split proposal, coming from the board of Vivendi, was attributable to a decision by Bolloré. Thus Article 236-6 of AMF rules would be applicable [ratione personae] (Bolloré had previously argued that it did not propose the split, the split having been proposed by the board of Vivendi). It also ruled that the split was a sufficiently “deep” change in the structure of Vivendi to make the rule applicable [ratione materiae]. And since, obviously, the rights of Vivendi shareholders were seriously impacted, a mandatory bid should have been made and required by the AMF.

so far, so much egg on its face. Now, what did it decide?

the facts regarding the control of Vivendi have not changed.

the AMF considers the current legal and factual situation should be taken into account, funnily basing its reasoning on rule 231-3 which states that “all persons concerned by a bid” (obviously, AMF included) should respect loyalty in transactions - and since it has no authority imposing a mandatory offer on Louis Hachette Group, Havas and Canal+ that came into existence after the split

imposes a mandatory bid on Vivendi SE in its present form.

Chaos Grenade

But it goes even further, with (in my view) MAJOR consequences that may not have been fully appreciated, and may well cause an even greater mess:

The AMF states that the treasury shares held by Vivendi, since it is “controlled” by Bolloré, should be included in Bolloré’s total shareholding. Thus Bolloré would exceed the 30% threshold and a mandatory offer applies. Please read that again. It is mind-boggling.

I am sure Bernard Arnault is having a cold sweat as we speak - because if this becomes the prevailing opinion, he may well be forced - right now - into a mandatory bid for LVMH.

A total tangent, but one worth more than a hundred billion Euros:

In the past 12 months:

LVMH has repurchased 2.8m shares (0.56% of outstanding shares)

Financière Agache has purchased 2.2m shares (0.45%)

Christian Dior SE has purchased 0.4m shares (0.08%)

so, if shares owned by the controlled company (and LVMH is beyond any doubt controlled by Bernard Arnault) are counted towards the total shareholding of the controlling shareholder, then Bernard Arnault has increased his shareholding of LVMH over the past 12 months by more than 1%. And this triggers a mandatory offer according to rule 234-5. This would be like tripping on the last few meters of a marathon - Arnault has been carefully buying LVMH stock for years in small doses not exceeding 1% per year, and is right now on the verge of crossing the 50% threshold into total freedom.

You see how this decision, if applied consequently, is likely to create a lot of chaos. And LVMH is only a very special case - in fact any controlled company that would repurchase more than 1% of its own shares within 12 months would risk triggering a mandatory bid. The opposite of a mistake is another mistake. And expect a lot of very hard lobbying against this interpretation - there are billions at stake, for France’s richest families.

A more sensible decision might be to scrap the “speeding” limit of 1% per year, which is not present in many other european countries’ bourse regulations. In any way, if not overruled by the supreme court, we are likely to see substantial changes in takeover regulations for the french market.

Offer terms

But let’s get back to Vivendi and Bolloré. The AMF ruled that Bolloré should not submit a mandatory bid, but well a delisting bid (offre publique de retrait, OPR) required by rule 236-6. This means that the share price is not a relevant criterion, but an independent expert should determine the value of the company. Bolloré has six months to submit its offer - but the AMF is careful enough to point out that it would make sure the offer only expires after the supreme court has issued a ruling regarding the appeals of Bolloré and Vivendi.

The valuation of Vivendi is relatively easy as a sum of its parts - a few details are, however, missing but we will know them soon as Vivendi is due to report its H1 results at the end of the month.

We can make a few assumptions regarding some movements:

Vivendi has most likely sold its entire shareholding in TIM by now (retaining a miniscule stake of 2.5% would not make sense given the strategic decision to exit the telecom market, and TIM share price has appreciated far beyond the price at which it first sold its majority stake).

Lagardère has refinanced its debt in June by issuing a 500m€ bond, thus there is a strong probability that Lagardère has repaid its Vivendi loan (500m€).

Vivendi has spent 282m€ in Q2 to acquire shares of Lagardère (mainly the 8% stake held by Financière Agache).

Vivendi has collected 92m€ in gross dividends from UMG, Banijay and Lagardère in Q2.

Anything else than a substantial reduction in debt at Vivendi would be a huge surprise. My current estimate of Vivendi’s NAV is around 5.4€. The independent expert can make some assumptions regarding privately held Gameloft, but it would be a rounding error - its current valuation of 234m€ is dwarfed by the listed portfolio which has a total value of around 6.5bn€.

Also, a US listing is contemplated for Universal Music Group (UMG). Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square had pushed for this move, but entities associated with him have since substantially reduced their stake. The offering is supposed to take place by September 15. Whether this will ultimately influence the share price of UMG will have to be seen - but if it happens it would impact Vivendi’s value since UMG is by far its main asset.

Un malheur n’arrive jamais seul (misfortune never comes alone)

it could seem like a conspiracy theory that on the same day that the AMF decision was announced, the European Commission released its own flavour of bad news for Bolloré and Vivendi - in the form of a “statement of objections”, accusing Vivendi of implementing the acquisition of Lagardère before its merger approval (so-called “gun jumping”). This could have dire consequences and lead to a fine of up to 10% of Vivendi’s turnover. Vivendi has issued its own press release and of course denies any wrongdoing:

Whatever the final outcome, there could be a silver lining: a provision for a potential fine (which may or may not have to be paid) could substantially reduce the net asset value of Vivendi and thus the consideration that Bolloré would have to pay in its forced bid.

Between jumping guns, wild decision reversals, financial acrobatics and the question whether of not thresholds have been touched in high-stakes high-jumps, this July has certainly treated us to a good dose of “Summer-saults”.

Excellent work. Thank you! Tough year for Vincent. First the Rivaud acquisitions were rejected by the AMF, then Vivendi, and now Lagardere jumping the gun. I do think Bollore family will win in the end, but they should move the company to the U.S. I now understand why the word bureaucracy is a French term.

great insights, thank you very much for writing this post